Jean Renoir

Figure 1. Auguste Renoir. Luncheon of the Boating Party, Bougival. 1881. Oil on canvas, 51 x 68” The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

Figure 2. Pierre Auguste Renoir. Oarsmen at Chatou. 1879. Oil on canvas. National Art Gallery, Washington DC.

Impression, Sunrise. Monet, 1872

Haystacks (Monet series), 1890-91

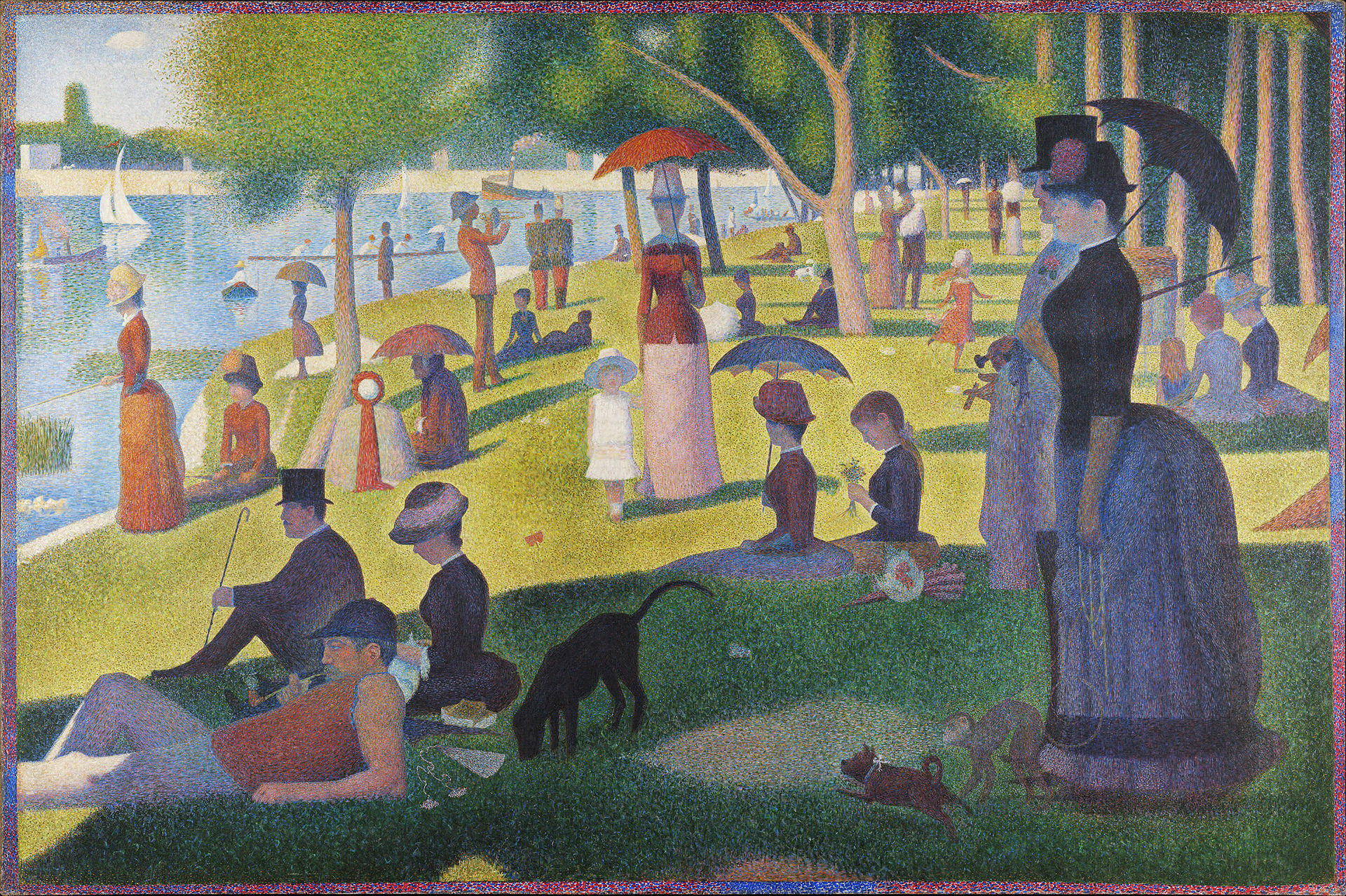

A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte,

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe, Édouard Manet (1862-1863)

Edgar Degas, Ballet, c. 1876–1877, pastel on monotype, 58.4 × 42.0 cm, Gift of Gustave Caillebotte, 1896. Musée d’Orsay, France.

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1906, oil on canvas, France.

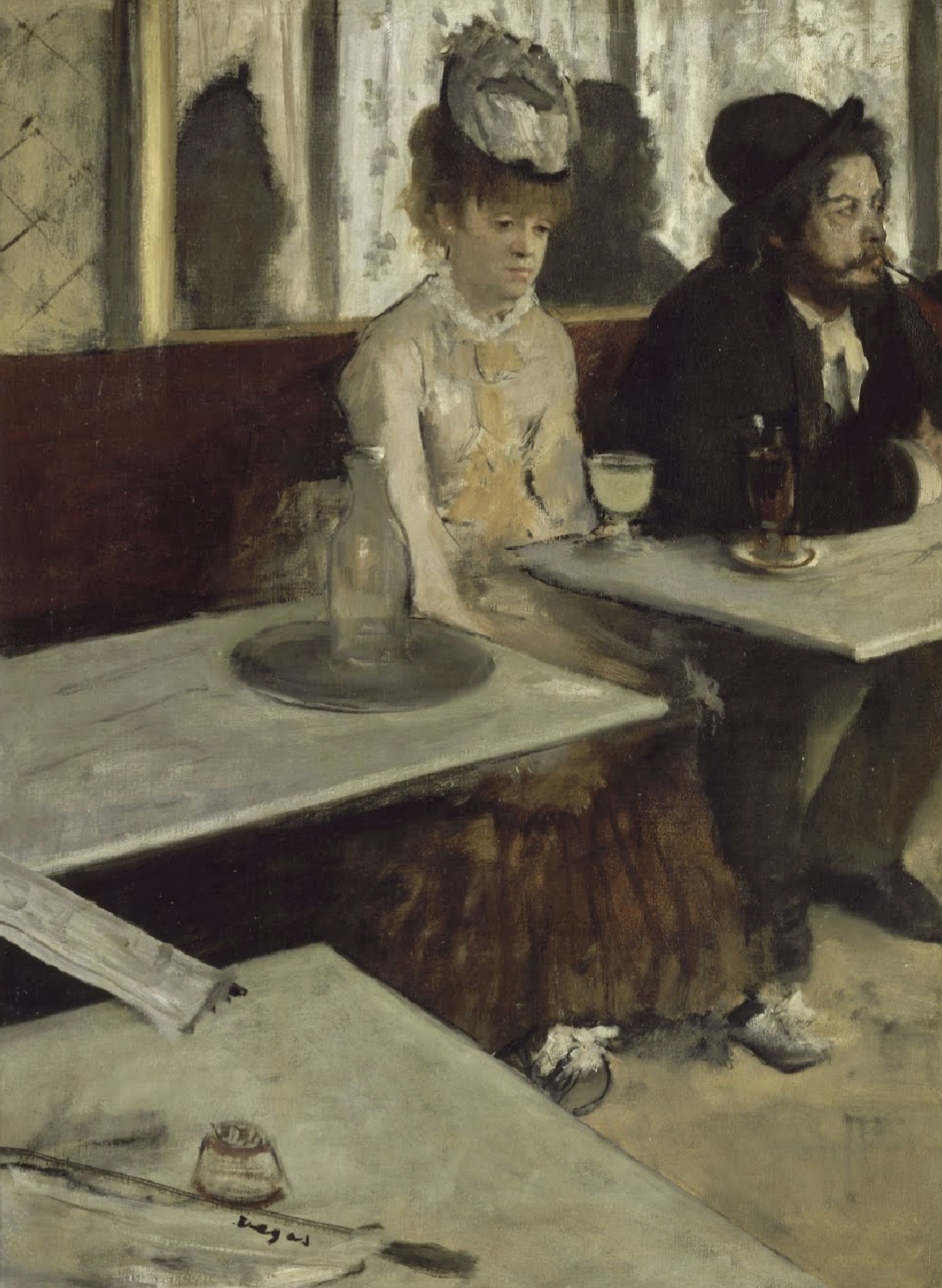

In a Café, Degas. 1876

Woman with a Parasol - Madame Monet and Her Son, Claude Monet, 1875

Bridge over a Pond of Water Lilies, Claude Monet, 1899

afé Terrace at Night, Vincent van Gogh, 1888,

The Cradle (1872) by Berthe Morisot.

Edouard Manet. A Bar at the Folies-Bergere. 1881-82. Oil on canvas, 37.5 x 51” (95.3 x 129.7 cm). Courtauld Institute Galleries, Home House Trustees, London.

The reserved Henriette & her flirtatious mother

The serious Henri & the carefree Rodolphe

The seemingly wise Monsieur Dufour & the awkward Anatole

Henri & Henriette

Romeo & Juliet

Pierre Auguste Renoir. Balançoire (The Swing, 1876) Oil on canvas. 92 x 73 cm. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

“As if all the trees on the bank were waving to her as she passed by.”

“She listened to the bird, lost in ecstasy.” “A nightingale! the music of the gods which accompanies human kisses.”